“‘Ted Bundy’ is to serial killers,” Bundy’s postconviction lawyer Polly Nelson once wrote, “as ‘Kleenex’ is to disposable handkerchiefs: The brand name that stands for all others.” In America, in the decades since Ted Bundy’s crimes, captures, trials, and resulting infamy, the term serial killer has itself become a kind of brand name for evil, one promising an ever-familiar fable about inhuman darkness disguised in human form, appearing out of nowhere, and terrorizing humanity until humanity can destroy it. “Justice has been on hold for a decade,” he announced, “and it’s about time that Ted Bundy paid for his crimes.” To the viewers across the country who tuned in to watch the countdown to Bundy’s execution, it was hard to imagine that the man whose name had become synonymous with the term psychopath deserved to draw another breath. He would answer their questions if they would advocate for his life.įlorida governor Bob Martinez remained unmoved.

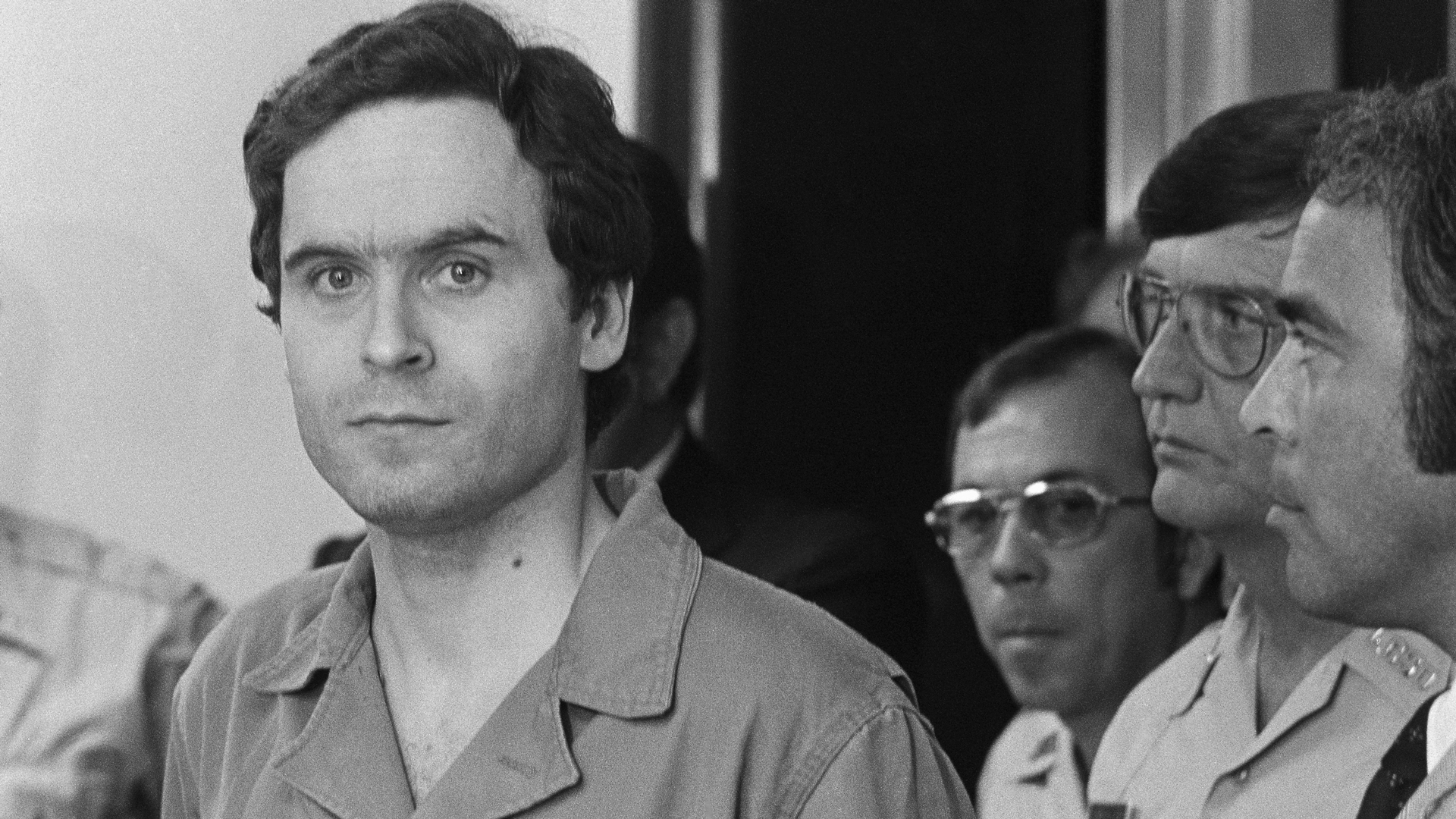

He needed a few more months to tell the whole story, he said, but he was willing to meet with investigators from around the country to show that he was serious. He would describe every murder he had committed, but only in exchange for a stay of execution. Then, as Florida restaurants put up signs advertising Bundy fries and Bundy barbecues and vendors stocked up on electric-chair-shaped lapel pins, Bundy said he was ready to confess-for a price. Ted Bundy was everywhere and nowhere, guilty of everything because he had admitted to nothing-nothing, that is, until the last few days before his scheduled execution. But Ted Bundy does what he wants to do when he wants to do it.” Holmes hadn’t taped either of his interviews with Bundy, but he didn’t need that kind of proof to convince people of what they already wanted to believe. “Ted Bundy knows the difference between right and wrong. “Ted Bundy is not insane,” Holmes told the press. Ron Holmes, a criminal justice professor who interviewed Bundy on two occasions, claimed that the total was 365, and that Bundy had raped and killed his first victim at the age of eleven. “He said the figure probably would be more correct in the three digits,” Deputy Sheriff Jack Poitinger said. Many said it had to be a hundred or more, and cited Bundy’s own enigmatic statement to the Pensacola detectives who had questioned him about the FBI’s claim. In the ensuing decade, both the random speculations of onlookers and the educated guesses of law enforcement often pushed the number far higher. When Ted Bundy was apprehended in Pensacola in the early hours of February 15, 1978, six weeks after he escaped from a Colorado jail, the FBI had already publicly linked him to thirty-six murders across five states. Now, in the early hours of January 24, 1989, it seemed Bundy’s time was finally about to run out. Ted Bundy had been on Florida’s death row for nearly a decade, after receiving three death sentences in two separate trials, for the 1978 murders of three victims who could be called young women but could also just as fairly be called girls: twenty-year-old Lisa Levy, twenty-one-year-old Margaret Bowman, and twelve-year-old Kimberly Leach. The shirts were selling particularly well, George said, among women. The words splashed above him read BURN BUNDY BURN. Printed in the bright red of cartoon blood, his T-shirts showed a sweating, wide-eyed man strapped into an electric chair, staring out at the viewer with an expression that managed to seem both helpless and imperious.

Within hours, George was doing a brisk business. “Do you think it’s appropriate,” a reporter asked him, “to be making money off some man’s execution?” His name was George Johnson, and when the camera crews found him, he was standing beside the trunk of his car, selling T-shirts for ten dollars apiece.

The throng had appeared as if from nowhere: the day before, there was only one man waiting outside Florida State Prison. Cochran said, “I thought it would be educational for them, kind of like a field trip.” They had brought their six-year-old twins, Jennifer and May Nicole, because, Mrs. One family, the Cochrans, told reporters they had left their home in Orlando, Florida at two o’clock in the morning so they could be sure not to miss the festivities. Celebrants lit sparklers, strangers joined in song, and children did their best to stay awake. Though dawn had not yet broken, the ground was littered with beer cans. Hundreds had gathered across the road from the prison, bundled against the midwinter chill and warming themselves with a clever vendor’s coffee and doughnuts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)